Ruptured Heterotopic Pregnancy

The Case

A 43-year-old woman, gravida 3 para 2, presented at 16 weeks' gestational age with abdominal pain. Her current pregnancy was the result of in vitro fertilization (IVF) with a donor egg. An outpatient ultrasound at 14 weeks was reportedly normal. On the day of presentation, she had experienced a sudden onset of severe lower abdominal pain followed by nausea and vomiting. Responding paramedics documented transient loss of consciousness and difficulty recording blood pressures en route to the emergency department (ED). In the ED, she was hypotensive and tachycardic with an initial spun hematocrit of 28. The ED physician performed an ultrasound, which showed an intrauterine pregnancy and free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. The ED physicians were concerned about a ruptured appendix.

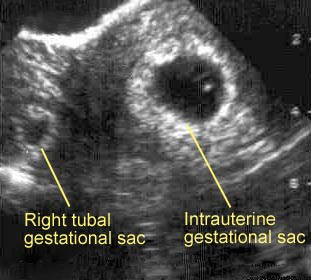

After surgery and obstetrics were informed of the patient, she was given IV fluids and sent to the CT scanner. The patient was seen in the CT scanner by the obstetrics resident, who after reviewing the history and noting the patient's appearance (hypothermic, tachycardic, and hypotensive), felt the patient was at high risk for a ruptured heterotopic pregnancy (a pregnancy in which one embryo implants inside the uterus and another is outside the uterus [Figure]). The patient was pulled out of the scanner and taken emergently to the operating room, where an exploratory laparotomy found a 12-week fetus in the right fallopian tube along with 4 liters of peritoneal blood.

The Commentary

Heterotopic pregnancies occur in approximately 1/5,000-1/10,000 pregnancies (1,2), and more than half are diagnosed in the operating room.(3) The heterotopic pregnancy rate in cycles utilizing assisted reproductive technologies (ART) (IVF and ovulation induction) is increased more than 100-fold, to 1%-3% (4,5), largely due to the presence of multiple embryos in a given cycle and the increased risk for tubal damage in an infertile population. Although the increasingly common practice of removing damaged tubes prior to ART has decreased this rate, the diagnosis of a heterotopic pregnancy should always be considered in this population.

While the index of suspicion may be raised in pregnancies resulting from ART, the common tools for diagnosis of ectopic gestations are of limited use. Diagnostic algorithms for ectopic pregnancies utilize ß-hCG levels, progesterone levels, and ultrasound to document an empty uterus. On the other hand, diagnostic testing in a patient with a heterotopic pregnancy will demonstrate the presence of a viable intrauterine pregnancy on ultrasound, increased ß-hCG levels, and progesterone levels within the normal range for pregnancy.

Clinicians caring for women who undergo ART should be familiar with the normal ranges for ß-hCG in their laboratory for a singleton gestation in early pregnancy (14-17 days after retrieval). An extremely high initial level or a more than typical doubling should heighten the suspicion for a multiple gestation and hence, a heterotopic pregnancy. Unfortunately, ß-hCG levels alone are not diagnostic as they may fall and rise in some situations, such as a "vanishing twin" (spontaneous resorption of one twin). The high risk of an ectopic pregnancy with ART (3%-5%) mandates early ultrasound (4 weeks post-transfer), performed by an experienced obstetrician or radiologist, to confirm the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy.(6)

Once an intrauterine pregnancy is identified, the adnexa should be carefully examined. The ovaries are frequently enlarged from ovarian hyperstimulation and may contain blood from a transvaginal retrieval. This common finding complicates the early identification of a heterotopic pregnancy, even with the best ultrasound skills and a high index of suspicion. Even in the absence of ART, an adnexal mass is not found in the presence of an ectopic pregnancy 15%-35% of the time.(6) Therefore, follow-up ultrasounds are critical and should be performed 2 weeks following the initial ultrasound. As the size of the pregnancy increases and the size of the ovaries decreases, the extra-uterine pregnancy may become more visible. However, 50% of heterotopic pregnancies are missed on ultrasound.(3) Non-specific symptoms may be attributed to the pregnancy itself and/or ovarian enlargement and may be thought to be self-limited, which could impede an early diagnosis even with a high index of suspicion.

In this case, the heterotopic was not "diagnosed" until 16 weeks' gestation. At this time, the patient's ovaries are generally small enough and the pregnancy large enough to reliably visualize the heterotopic when the adnexa are carefully examined. The absence of visualization of an extra-uterine gestational sac earlier in the pregnancy may have falsely reassured her outpatient physicians. However, upon presentation—with the history of loss of consciousness and symptoms to suggest hemodynamic instability—the presence of peritoneal fluid should have prompted a more detailed evaluation of the pelvis by ultrasonography. Obstetric residents receive early pregnancy ultrasound training and have heightened awareness of ectopic gestations as a result of regularly following and caring for these pregnancies. If emergency department physicians are to be the first line of defense in recognizing ectopic pregnancies, they should be trained in early pregnancy scans and be aware of the increased risk in patients utilizing ART. Even following ART, diagnosis of a heterotopic pregnancy will still be occasionally missed until rupture is evident.

This heterotopic pregnancy was diagnosed late, which may have further complicated its course in the ED. More than 85% of heterotopic pregnancies are tubal (3), and tubal pregnancies very rarely go into the second trimester without rupture.(6) That the pregnancy was reportedly at 16 weeks’ gestation may have falsely reassured the ED physician regarding an ectopic gestation.

In this case, the biggest concern is the transfer of an unstable patient to the CT scanner. In the presence of hemodynamic instability and free fluid in the pelvis, this patient should have been resuscitated with IV fluids and blood products and sent directly to the operating room for exploratory laparotomy. No further testing would have added to the clinical picture.

Diagnosing a heterotopic pregnancy is not easy, and delayed diagnoses will continue to occur. However, the current rate of missed diagnosis is too high. While treatment is complicated given the presence of a coexistent intrauterine pregnancy, earlier diagnosis would allow for less invasive procedures and potentially eliminate the need for blood products. The most important factor in preventing cases like this one is early diagnosis of the heterotopic pregnancy.

Take-Home Points

- In patients undergoing infertility treatments, there should be a high index of suspicion for both ectopic and heterotopic pregnancies.

- The presence of ovulation induction, with multiple resultant mature ova, with or without IVF, should increase the suspicion for a heterotopic pregnancy.

- The initial level of ß-hCG and its early pattern of rise may further raise the index of suspicion and be helpful if clinicians are familiar with expected levels.

- Following embryo transfer, initial ultrasound should be performed no later than 4 weeks. Even in the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy, the adnexa should be examined. Follow-up examination should be performed 2-3 weeks later, when the ovaries should be decreasing in size.

- Earlier evaluation should be performed for abdominal pain and/or non-specific GI complaints. Emergency physicians should have added training in early pregnancy ultrasound.

- Following ART, if a pregnant patient is hemodynamically unstable, she should be considered to have a ruptured extrauterine pregnancy and taken for exploratory laparotomy.

Marcelle I. Cedars, MD Director, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility Director, Embryology Laboratory University of California San Francisco

References

1. Dumesic DA, Damario MA, Session DR. Interstitial heterotopic pregnancy in a woman conceiving by in vitro fertilization after bilateral salpingectomy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:90-2.[ go to PubMed ]

2. Lau S, Tulandi T. Conservative medical and surgical management of interstitial ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:207-15.[ go to PubMed ]

3. Heard MJ, Buster JE. Ectopic pregnancy. In Scott JR, Gibbs RS, Karlan BY, Haney AF, eds. Obstetrics and gynecology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2003.

4. Dor J, Seidman DS, Levran D, Ben-Rafael Z, Ben-Shlomo I, Mashiach S. The incidence of combined intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:833-4.[ go to PubMed ]

5. Ikeda S, Sumiyoshi M, Nakae M, Tanaka S, Ijyuin H. Heterotopic pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1998;77:463-4.[ go to PubMed ]

6. Ankum WM, Van der Veen F, Hamerlynck JV, Lammes FB. Transvaginal sonography and human chorionic gonadotrophin measurements in suspected ectopic pregnancy: a detailed analysis of a diagnostic approach. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:1307-11.[ go to PubMed ]

Figure

Figure. Ultrasound Image of Heterotopic Pregnancy.