Where's the Feeding Tube?

Metheny NA, Meert KL. Where's the Feeding Tube?. PSNet [internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2008.

Metheny NA, Meert KL. Where's the Feeding Tube?. PSNet [internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2008.

The Case

A 13-year-old boy was involved in a motor vehicle collision and experienced a traumatic brain injury. Because of the injuries, he was unable to swallow and had to receive nutrition through a nasojejunal feeding tube. After many weeks in the intensive care unit (ICU), he was transferred to a rehabilitation unit with improved mental status. A routine chest radiograph performed to check for resolution of a pneumothorax (punctured lung) revealed that the nasojejunal tube had migrated, and the tip was now in the gastric area (serving as a nasogastric feeding tube). The medical team felt that this placement was adequate, and the boy continued to receive enteral feedings.

Two days later, the boy developed tachycardia (increased heart rate), tachypnea (increased respiratory rate), and decreased oxygen levels that required supplemental oxygen. A portable chest radiograph revealed evidence of pneumonia. In addition, the chest radiograph showed the nasogastric tube had moved again, and the tip was now in the esophagus. Given the more proximal location of the nasogastric tube, physicians felt that the pneumonia was most likely from an aspiration event (inhalation of the liquid food into the lungs).

Because of decreasing oxygen levels and worsening mental status, the patient required transfer back to the ICU. He was treated with antibiotics and supportive care and slowly improved. He returned to the rehabilitation center 3 days later, but unfortunately his mental status and physical state had declined since before the aspiration event. His recovery was delayed, and the aspiration event caused significant emotional distress for his family.

The Commentary

Like many adult and pediatric patients who are unable to eat normally, frequently due to poor mental status or mechanical difficulties in swallowing, the patient in this case had a feeding tube placed. Tube feeding is favored over parenteral (intravenous) feeding in patients of all ages, provided the gut is functional. Because of its many advantages, tube feeding is commonly used in both acute and long-term care settings. In 1994, the prevalence of tube feeding in nursing home residents ranged from 7.5% in Maine to 40.1% in Mississippi.(1)

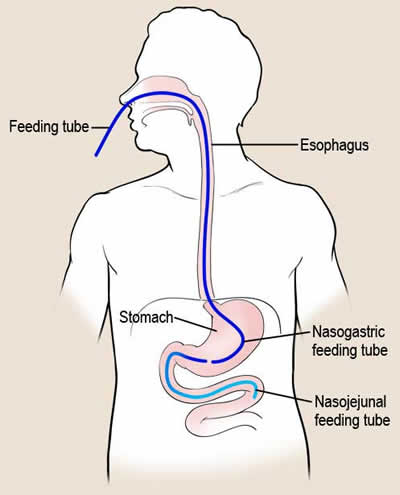

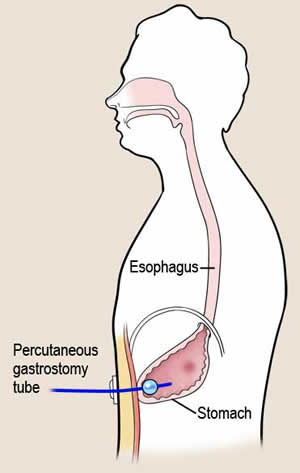

Numerous types of tubes can be used for enteral feeding. Patients who require short-term (less than 1 month) feeding often have tubes placed directly through the nose into the gastrointestinal tract. These feeding tubes are thin (often less than 2 mm in diameter) and flexible to maximize patient comfort. As described in this case, these tubes can either end in the stomach (nasogastric [NG] tube) or in the small intestine (nasojejunal tube) (Figure 1). For those patients who require longer-term feeding, percutaneous gastrostomy tubes are favored. These tubes enter directly through the skin into the stomach (Figure 2). They generally cause less discomfort than nasally or orally placed tubes (2) but do not decrease the risk of aspiration of stomach contents. Note that these tubes should be distinguished from the larger-bore (often 5-7 mm) NG tubes that are typically used to suction out stomach contents. These larger NG tubes should generally not be used for feeding for more than a few days, as they predispose to sinusitis and an increased risk of pneumonia.(3) (Problems with NG tubes were also discussed in a previous AHRQ WebM&M commentary.)

The above case report provides an opportunity to discuss some of the challenges in managing NG feeding tubes and specifically, the problems with accurately determining tube location. We are told that the NG feeding tube had migrated from the patient's small bowel into the esophagus. The displacement of the tube could have occurred in one of two ways. The tube could have been partially pulled out of the nose (causing the external length of tubing to be visibly increased), or the distal tip of the tube could have migrated upward without any outward indication following a bout of vomiting or coughing. Dislodgement of feeding tubes is a common problem, especially in restless patients and those who are confused and may inadvertently pull on the feeding tube. While taping to the nasal bridge is the most frequently used method to secure feeding tubes, some clinicians prefer to use the bridle technique to anchor small-bore nasoenteric tubes in patients at high risk for unintentional tube removal.(4) With this technique, the feeding tube is secured to tubing that is placed around the back of the nasopharynx and exits both nostrils.

Most reports of malpositioned feeding tubes involve inadvertent placement into the respiratory tract during blind insertions. However, a tube with feeding ports in the esophagus is also defined as malpositioned because it significantly increases risk for aspiration, as seen in the above case study. It is thus appropriate that most facilities require radiographic confirmation that a newly inserted feeding tube's ports are not positioned in the respiratory tract or esophagus.(5)

What could have been done to detect this child's malpositioned tube before it led to aspiration? For practical and radiation exposure reasons, chest radiography cannot be used several times a day to check tube location; thus, clinicians are forced to rely on a variety of bedside methods (described below). When bedside tests raise concern about tube location during feedings, a radiograph should be ordered as the best test to determine precise tube location in the gastrointestinal tract.

In acute and critical care settings, bedside assessments to check tube location are typically made at 4-hour intervals. Many upwardly displaced tubes are detected when clinicians notice an increase in a feeding tube's external length outside the nose.(6) Once properly positioned and secured, a simple mark can be made on the tube at a known distance from the nose (e.g., 5 cm). Then, the distance between the mark and the naris can be measured periodically to check for outward migration. In patients with feeding tubes in acute or critical care settings, the residual volume, the amount of feeding solution remaining in the stomach, is measured routinely (every 4 hours) to assess aspiration risk. (If the patient is receiving continuous feedings, the feeding is interrupted only as long as necessary to withdraw fluid into a syringe for measurement; if the patient is receiving intermittent feedings, the residual volume is measured by syringe immediately before the next feeding is administered.) A sharp increase in residual volume may indicate displacement of a small-bowel tube into the stomach. Consistent inability to withdraw fluid from the feeding tube may signal upward displacement into the esophagus. In addition, because gastric pH is lower than small-bowel pH, testing the pH of feeding tube aspirates may be helpful in detecting tube dislocations during intermittent feedings, but not as much during continuous feedings because enteral formula buffers the pH of gastrointestinal secretions.(7) Reviewing tube position on radiographs performed for other diagnostic or treatment purposes is also recommended. Radiologists often refer to tube location in their reports.

Auscultation of the abdomen with a stethoscope to determine position in the stomach was used frequently in the past but has fallen from favor because of multiple reports of its inability to accurately determine tube location.(8,9) While a carbon dioxide detector may help determine if a blindly inserted tube has entered the respiratory tract (as opposed to the gastrointestinal tract), it cannot determine if the tip of the tube ends in the esophagus, stomach, or small bowel.

We are also told in this case report that the clinicians were satisfied with the feeding tube in the stomach and did not require it to be in the jejunum (small bowel). There is little consensus on the optimal feeding site to prevent aspiration. However, there is general agreement that distal small-bowel feedings are preferred when patients are intolerant of gastric feedings or have had documented aspiration events in the past. Some clinicians prefer to start with small-bowel feedings in patients at high risk for aspiration, especially when unit personnel are skilled in small-bowel tube insertions. The use of prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide or erythromycin, within minutes before feeding tube insertion increases the probability of achieving small-bowel feeding tube placement.(10,11)

In addition to determining tube placement, a number of other problems with NG feeding tubes are worth mentioning. All tubes, regardless of insertion type, can become clogged. This complication can be prevented by regularly flushing the tube with water and following guidelines for administering medications via the feeding tube. A mixture of pancreatic enzymes and sodium bicarbonate may be the most effective way to clear a clogged feeding tube.(12) Connections among different tubes can be mishandled: The inadvertent connection of an enteral feeding solution into a nonenteral system, such as an intravascular line or peritoneal dialysis catheter, can result in sepsis and death. An expert panel has recently published a set of guidelines to prevent this potentially lethal problem.(13) Among their recommendations are using enteral connectors that are not compatible with intravenous connectors, clearly labeling tube feeding formulas as "for enteral use only," and tracing lines back to their origins before their reconnection.

The pediatric patient in this case did not experience any long-term consequences, but the feeding tube migration and aspiration event could potentially have been prevented by simple bedside assessments. Hospitals and care facilities should consider creating checklists or other standard mechanisms to make sure that feeding tube position is routinely monitored.

Take-Home Points

- Obtain radiographic confirmation that a blindly inserted feeding tube is properly positioned before its initial use.

- Assess tube location every 4 hours by observations for changes in the length of tubing extending from the insertion site as well as in the amount of fluid withdrawn from the tube during residual volume measurements.

- Use small-bowel feedings when patients are intolerant of gastric feedings or have documented aspiration.

- Flush feeding tubes with water at regular intervals to prevent clogging.

- Adhere to guidelines to prevent inadvertent connection of an enteral feeding into a nonenteral system.

Norma A. Metheny, RN, PhD Professor of Nursing Dorothy A. Votsmier Endowed Chair Saint Louis University, School of Nursing

Kathleen L. Meert, MD Professor of Pediatrics Wayne State University School of Medicine Pediatric Critical Care Medicine Specialist

Children's Hospital of Michigan, Detroit

References

1. Ahronheim JC, Mulvihill M, Sieger C, Park P, Fries BE. State practice variations in the use of tube feeding for nursing residents with severe cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:148-152. [go to PubMed]

2. Metheny NA, Clouse RE, Chang YH, et al. Tracheobronchial aspiration of gastric contents in critically ill tube-fed patients: frequency, outcomes, and risk factors. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1007-1015. [go to PubMed]

3. Bert F, Lambert-Zechovsky N. Sinusitis in mechanically ventilated patients and its role in the pathogenesis of nosocomial pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:533-544. [go to PubMed]

4. Popovich MJ, Lockrem JD, Zivot JB. Nasal bridle revisited: an improvement in the technique to prevent unintentional removal of small-bore nasoenteric feeding tubes. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:429-431. [go to PubMed]

5. Baskin WN. Acute complications associated with bedside placement of feeding tubes. Nutr Clin Pract. 2006;21:40-55. [go to PubMed]

6. Metheny NA, Schnelker R, McGinnis J, et al. Indicators of tubesite during feedings. J Neurosci Nurs. 2005;37:320-325. [go to PubMed]

7. Gharpure V, Meert KL, Sarnaik AP, Metheny NA. Indicators of postpyloric feeding tube placement in children. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2962-2966. [go to PubMed]

8. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Verification of feeding tube placement. Aliso Viejo, CA: American Association of Critical-Care Nurses Practice Alert; May 2005. Available at: http://classic.aacn.org

9. National Patient Safety Agency. How to confirm the correct position of nasogastric feeding tubes in infants, children and adults. London, UK: National Health Service. February 22, 2005. Available at: http://www.npsa.nhs.uk/EasySiteWeb/GatewayLink.aspx?alId=3399

10. Lee AJ, Eve R, Bennett MJ. Evaluation of a technique for blind placement of post-pyloric feeding tubes in intensive care: application in patients with gastric ileus. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:553-556. [go to PubMed]

11. Phipps LM, Weber MD, Ginder BR, Hulse MA, Thomas NJ. A randomized controlled trial comparing three different techniques of nasojejunal feeding tube placement in critically ill children. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2005;29:420-424. [go to PubMed]

12. Marcuard SP, Stegall KS. Unclogging feeding tubes with pancreatic enzyme. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1990;14:198-200. [go to PubMed]

13. Guenter P, Hicks RW, Simmons D, et al. Enteral feeding misconnections: a consortium position statement. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:285-292. [go to PubMed]

Figures

| Figure 1. Nasogastric and nasojejunal feeding tube placement. Figure 2. Percutaneous gastrostomy tube. |