Rapid Mis-St(r)ep

The Case

A 5-year-old girl was brought to an urgent care center by her father with a 2-day history of fever to 103°F, sore throat, and diffuse abdominal pain. There was no history of cough or runny nose. On examination, she appeared ill and had a temperature of 101°F. Her posterior oropharynx was erythematous without exudates, and the tonsils were not enlarged. She had tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy. The remainder of the examination, including the abdominal examination, was unremarkable.

With concern for strep throat, the urgent care physician swabbed the child's throat and performed a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) in the clinic. The "rapid strep test" was interpreted as negative. A culture of the posterior oropharynx was not performed. Urinalysis revealed 3+ ketones and a specific gravity (SG) >1.030. The child was given a diagnosis of viral syndrome and dehydration, and the father was reassured. He was advised to give her antipyretics and extra water and juice and to observe her closely for adequate urine output or worsening of symptoms.

Four hours later, the child appeared more ill to the father and developed a fever of 104°F. Concerned, the father took the child to the nearest emergency department (ED). In the ED, she had a fever of 103.5°F and an erythematous posterior oropharynx and tender lymphadenopathy on examination. The ED physician repeated the RADT. The result was strongly positive for group A streptococcal infection. The child was treated with oral amoxicillin and was afebrile with minimal sore throat 2 days later.

The Commentary

This 5-year-old with a sore throat illustrates an issue faced millions of times in the United States each year. Streptococcal pharyngitis/tonsillitis is among the most common illnesses seen by primary care physicians. The importance of this infection is evidenced by the many guidelines published by professional societies not only in the United States, but around the world.(1-3) Despite this attention and a far greater understanding of the microbiology and epidemiology of group A streptococci (Streptococcus pyogenes), there has been essentially no "translation" (to use the current buzzword) of the results of laboratory research to everyday clinical management of streptococcal pharyngitis during the past half-century. Parents still bring their children with a sore throat to the clinician for a throat swab and are often given an antibiotic indiscriminately (most often a penicillin). Essentially no change in management has occurred!

The clinical diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis is frequently difficult, in part because patients don't always present with classic signs and symptoms.(4,5) Moreover, presenting symptoms vary with the age of the patient.(4) For example, this 5-year-old had the classic clinical presentation for school-age children, who tend to present with anterior cervical lymphadenitis (tender lymph nodes) and abdominal pain. Further adding to the management challenge, many patients with a viral upper respiratory tract infection will also be concomitant carriers of group A streptococci.(5) Given these factors, published clinical algorithms are often imperfect in making the diagnosis and guiding appropriate therapy.

As patients usually improve symptomatically even without antibiotic therapy, the goal of antibiotic therapy for streptococcal pharyngitis is eradication of the organism from the throat. Eradication is necessary to prevent nonsuppurative sequelae such as rheumatic fever in infected individuals.

Although the amoxicillin given to this child is identical or similar to that recommended by most clinical guidelines, therapy can be problematic. While there has never been a group A streptococcal clinical isolate that has shown resistance to penicillin(s) (7), penicillin's bitter taste is such that children do not like to ingest it, leading many clinicians to prefer the more palatable amoxicillin suspension. Recent support by some for short-course antibiotic therapy (fewer than 10 full days of a penicillin or cephalosporin, macrolide, or azalide) remains controversial and has not been included in most current guidelines in the United States. At the present time, a full 10-day course of most antibiotics is recommended in most authoritative guidelines.(1-3)

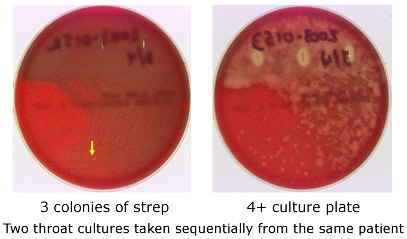

Perhaps a practical, clinically adaptable advance in management of group A streptococcal infection of the throat is RADTs for group A streptococci. One problem with RADTs is illustrated by the patient presented here. Studies during the past 20 years indicate that the specificity (i.e., the ability of a positive test to detect the presence of group A streptococci) of these tests is much better than the sensitivity (the ability of a negative test to exclude the presence of group A streptococci). That is, if the rapid strep test is positive, the patient likely has a group A streptococcal infection, but a negative test does not rule out the infection. Since essentially all rapid streptococcal tests are based upon an antigen-antibody reaction involving the group-specific carbohydrate of the cell wall, a sufficient number of organisms must be present on the swab in order to result in a "positive" test. This means that insufficiently thorough swabbing of the pharynx/tonsils and/or a relatively low organism load in the throat can result in falsely negative results. Sampling error (Figure) is one key reason why authoritative sources and major guidelines recommend that if a rapid test is negative, a concomitant culture should be carried out.

False-positive throat RADTs also occur, but these are much less common. One documented cause for a falsely positive rapid test is related to the fact that some strains of Streptococcus milleri, a common part of the oral flora, carry the group A carbohydrate antigen on their surface and thus react positively with the usual commercially available RADT for Streptococcus pyogenes.(8) These false positives are rare and should not affect clinical management. A positive RADT should result in antibiotic therapy for patients with consistent signs and symptoms. Some clinical microbiology laboratories may overlook or incorrectly identify the presence of group A streptococci on agar plates; this possibility is recognized.(9)

In this case, the physician was concerned about the possibility of streptococcal pharyngitis. There are only two aspects of the medical care that one might question. The presence of tender anterior cervical lymph nodes is a very important clinical finding and has been correlated with true streptococcal infection.(5) This should have emphasized the need for a back-up agar plate culture. When one suspects streptococcal infection, a strep culture should be sent even when the RADT is negative. In retrospect, the initial rapid test may have been negative due to a sampling issue. The sample obtained on the swab may not have been sufficiently representative to trap an adequate number of streptococci to allow the rapid test to disclose their presence. When swabbing the tonsils and posterior pharynx, care should be taken to avoid the tongue. The swab is then moved back and forth across the posterior pharynx, tonsils, or tonsillar fossae. The physician appropriately advised the parent to return if the child's symptoms worsened.

The presented case illustrates several clinical and laboratory issues that remain controversial and result in variation in the medical management of streptococcal tonsillitis and pharyngitis. In the future, a cost-effective streptococcal vaccine may become available to assist in the control of this infection and its sequelae. Until then, more "translational" research is needed to improve both the medical care of patients with streptococcal tonsillitis/pharyngitis and the public health approaches to this common infection and its sequelae.

Take-Home Points

- Because of variable symptoms and microbiologic factors, the diagnosis and appropriate therapy of group A streptococcal pharyngitis remain challenging.

- While frequently used, it must be remembered that the specificity of rapid antigen detection tests is much better than the sensitivity. Most guidelines recommend that if the rapid test is normal in a patient with a compatible illness, a back-up throat culture be done.

- Inadequate sampling of the posterior oropharynx can lead to false-negative results on rapid strep tests or streptococcal cultures.

Edward L. Kaplan, MD Professor of Pediatrics Department of Pediatrics University of Minnesota Medical School

References

1. Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM Jr, Kaplan EL, Schwartz RH, for the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:113-125. [go to PubMed]

2. Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Long SS, McMillan JA, eds. Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2006.

3. Dajani A, Taubert K, Ferrieri P, Peter G, Shulman S. Treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis and prevention of rheumatic fever: a statement for health professionals. Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the American Heart Association. Pediatrics. 1995;96:758-764. [go to PubMed]

4. Wannamaker LW. Perplexity and precision in the diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis. Am J Dis Child. 1972;124:352-358. [go to PubMed]

5. Kaplan EL, Top FH Jr, Dudding BA, Wannamaker LW. Diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis: differentiation of active infection from the carrier state in the symptomatic child. J Infect Dis. 1971;123:490-501. [go to PubMed]

6. Kaplan EL, Johnson DR. Unexplained reduced microbiological efficacy of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G and of oral penicillin V in eradication of group a streptococci from children with acute pharyngitis. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1180-1186. [go to PubMed]

7. Macris MH, Hartman N, Murray B, et al. Studies of the continuing susceptibility of group A streptococcal strains to penicillin during eight decades. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:377-381. [go to PubMed]

8. Johnson DR, Kaplan EL. False-positive rapid antigen detection test results: reduced specificity in the absence of group A streptococci in the upper respiratory tract. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1135-1137. [go to PubMed]

9. Johnson DR, Kaplan EL, Sramek J, et al. Laboratory Diagnosis of Group A Streptococcal Infections: A Laboratory Manual. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1996.

Figure

Figure. Example of Sampling Error in Throat Cultures. Two swabs were taken from the same child within 20 seconds and immediately plated onto appropriate agar. One swab (right) resulted in a strongly positive plate, while the other (left) led to only three colonies on the plate [in the photo, only one can be seen clearly (arrow)]. This weakly positive culture almost certainly would have resulted in a negative rapid antigen detection test, yet the organisms can be detected on the culture plate. (Slide by Edward L. Kaplan, MD; 2003.)