Neurological Red Flags: A Missed Stroke after Intermittent Episodes of Dizziness and Headache

Edlow J. Neurological Red Flags: A Missed Stroke after Intermittent Episodes of Dizziness and Headache. PSNet [internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2024.

Edlow J. Neurological Red Flags: A Missed Stroke after Intermittent Episodes of Dizziness and Headache. PSNet [internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2024.

Debra Bakerjian, PhD, APRN, RN; David Barnes, MD; Jonathan Edlow, MD, FACEP and Patrick Romano, MD, MPH, for this Spotlight Case and Commentary have disclosed no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies related to this CME activity.

Learning Objectives

At the conclusion of this case, participants should be able to:

- Categorize causes of acute dizziness using the “timing and triggers” approach.

- Sort patients into the acute vestibular syndrome or the episodic vestibular syndrome and know the most common diagnoses within each.

- Appreciate that dizziness “plus” other neurological symptoms is more likely to be caused by a central (as opposed to peripheral) etiology.

- List the typical vascular causes of posterior circulation transient ischemic attack and ischemic stroke in younger patients.

- Recognize the limitations of acute brain imaging in patients with posterior circulation cerebral ischemia or infarction.

The Case

A patient in his mid-30s with no significant past medical history other than some recent dental work presented to an emergency department (ED) with 3 weeks of intermittent left-sided headaches associated with listing or leaning to the left. On the day of presentation, he awoke with the same headache and balance issues but also about 15 minutes of difficulty speaking and moving, both of which resolved before arrival at the hospital. Vital signs were normal, and the ED provider also documented a normal neurologic exam, including normal finger-nose, heel-shin, balance, and tandem gait testing. Nystagmus was not documented but no maneuvers were performed. The electrocardiogram, blood chemistries, and complete blood count were all normal. Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the head was reported as normal, although later evaluation identified subtle abnormalities that were missed. No neurology consultation was obtained. The patient was discharged home with neurology follow-up and a final diagnostic impression of headache, dizziness, and sleep paralysis.

About 5 hours after being discharged from the ED, the patient’s wife witnessed him posturing or possibly having seizures and called 911. He required intubation in the field due to decreased consciousness and hypoventilation. The new ED physician at the same hospital documented no withdrawal to pain but some left arm motion. A stroke code was not initiated, but neurology was consulted. Repeat head CT showed evidence of a stroke in the left occipital lobe; CT angiography showed occlusion of the distal left posterior cerebral artery with suspected dissection of the left vertebral artery. An MRI showed multiple posterior circulation infarcts of various ages. About 6 hours after arrival, the patient was transferred to an interventional stroke center, which performed emergent thrombectomy, without any immediate improvement. The patient was left with a severe neurologic deficit.

The Commentary

By Jonathan A. Edlow, MD, FACEP

This patient’s initial ED presentation contains several key features that need to be accounted for in the diagnosis and medical decision-making:

- The patient is a young healthy individual

- Neurological symptoms occurred intermittently over 3 weeks

- The problem with balance was accompanied by headache, and later by difficulty moving and speaking

- The neurological examination as documented was normal

- A non-contrast CT scan of the head was reported to be normal

The History

Focusing on the “balance issues” helps to anchor an approach to this patient’s diagnosis. Balance issues fall under the more general category of dizziness, a broad term that has traditionally been divided into “vertigo” (illusory sense of motion, often spinning), “lightheadedness” (feeling of impending faint, especially on sitting or standing up), “imbalance” (a sensation of disequilibrium, especially when walking, usually perceived as in the body, as opposed to the head). Because sensory symptoms are frequently difficult for patients to describe and because some patients are unable to place themselves into one of these descriptive categories, a fourth category of “other” is also used.

This traditional “symptom quality” approach to diagnosing patients with isolated dizziness, used for decades and taught across specialties, placed a premium on these descriptive terms.1 Using this approach, clinicians asked the patient, “What do you mean, ‘dizzy’?” and the patient’s response drove the differential diagnosis and testing (see Table 1).

Table 1. Symptom Quality Approach to Diagnosis of Acute Dizziness

| Descriptive term | Usual diagnostic implication |

| Vertigo | Implies an inner ear cause |

| Lightheadedness | Implies a cardiovascular cause |

| Imbalance | Implies a neurological cause |

| Other | Implies a psychosocial cause |

| Source: Drachman and Hart (1972) | |

However, accumulating research findings from the last 20 years have called this “symptom quality” approach into question. Patients in the ED with dizziness change their descriptive word 50% of the time, even when requestioned less than 10 minutes later, and often endorse multiple descriptors simultaneously.2,3 These findings largely undercut the logic of the symptom quality approach. “Vertigo” can be seen with benign causes of dizziness like benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) or vestibular neuritis, but also with posterior circulation stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA). Furthermore, patients with BPPV often complain of non-specific dizziness,3 and some patients with cardiovascular causes of dizziness (who “should” endorse “lightheadedness”) describe vertigo.4 Thus, the specific word that a patient uses (e.g., “dizziness”, “vertigo”, “imbalance”, “lightheadedness” and others) is not as diagnostically useful as once thought. The patient in this case endorsed “imbalance”, but the clinician should be thinking of the differential diagnosis of “dizziness”.

What system should replace the traditional paradigm?

A history-taking approach based on the duration of episodes of dizziness and their identified triggers, known as the “timing and triggers” approach (Table 2), is more consistent with the existing evidence than the traditional paradigm.5,6 Furthermore, it is really no different than how clinicians take histories in most other patients.7 For example, the symptom quality of “sharp tearing” chest pain suggests aortic dissection; however, a patient with intermittent episodes of “sharp tearing” chest pain that only occurs with walking upstairs carrying groceries and resolves within minutes of rest is most likely new onset angina, not a dissection. Symptom timing and triggers influence the diagnosis. Education on the “timing and triggers” approach not only improves diagnostic accuracy, but seems to result in improved clinician satisfaction, especially as it relates to BPPV diagnosis.8,9,10 Using a logical, evidence-based algorithmic approach more often leads to a confident, specific diagnosis for the cause of dizziness.

Table 2. Timing and Triggers Approach to the Diagnosis of Acute Dizziness

| Syndrome | Description | Benign causesa | Serious causesa |

| Acute vestibularb syndrome | Rapid onset of persistent continuous dizziness, usually accompanied by nausea, vomiting, head-motion intolerance and often nystagmus | Vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis, medication adverse reaction | Posterior circulation stroke |

Triggered episodic vestibularb syndrome | Brief episodes of dizziness that are reproducibly triggered by something, usually movement of the head or body | BPPV, orthostatic hypotension (benign causes) | Orthostatic hypotension (serious causes) |

Spontaneous episodic vestibularb syndrome | Episodes of varying duration of dizziness that are not triggered by anything and “come out of the blue” | Vestibular migraine, Meniere disease | Posterior circulation transient ischemic attack (TIA) |

Source: Edlow et al. (2018); Gurley and Edlow (2020) a This table lists the more common causes in an emergency department or primary care practice.A fourth category not covered in this table, the chronic vestibular syndrome, also occurs and is more commonly caused by anxiety and depression or medication side-effects. bThe word “vestibular” refers to the nature of the symptom and not necessarily its anatomic substrate. These “vestibular syndromes” could be named “dizziness syndromes”; however, because the nomenclature originates from the neuro-otology literature, “vestibular syndromes” is how they are typically named. They are often due to pathology of the peripheral vestibular apparatus or its central connections. However, a patient with acute-onset dizziness from an antiepileptic drug might present with an “acute vestibular syndrome”, or another with orthostatic hypotension from a mild gastrointestinal bleed may present with a “triggered episodic vestibular syndrome”. | |||

In addition to the timing and triggers of any presenting symptom, context is important. There are four additional elements embedded in this patient’s history that should have been considered.

The first is that the patient was a young individual without traditional vascular risk factors. Although strokes are far more common in older persons with vascular risk factors (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, tobacco use, dyslipidemia and others), approximately 15% of ischemic strokes occur in patients < 50 years of age.11 Posterior circulation strokes may be more common in younger patients.12 In a consecutive series of over 1000 Finnish stroke patients aged 15-49, cervical artery dissection accounted for 15%.12 By contrast, in a study of 1368 patients of all ages with stroke, only 2% were caused by dissection.13 Other important stroke mechanisms in young patients include cardioembolism, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, hypercoagulable states and others.11

Young patients with cardioembolic strokes often have venous thromboses that traverse a patent foramen ovale, which is present in approximately 25% of the population.14 Hence, a stroke evaluation in young patients often includes a cardiac echocardiogram with a bubble study to rule out right-to-left shunt. Cervical artery dissections can occur spontaneously or after head or neck trauma, which can be minimal, and can present with isolated headache or neck pain from the intimal arterial tear, or with an acute neurological deficit if intraluminal clot obstructs blood flow to the brain.

The second contextual element is the recent dental procedure. Multiple patients with cervical artery dissection, some complicated by posterior circulation stroke, have been reported during or after dental procedures, a trip to the beauty parlor, or chiropractic treatments.15,16,17,18,19 The common denominator for these activities is neck hyperextension, although a direct causal relation is unclear.20

The third element is that the patient did not have isolated dizziness but rather dizziness “plus” other symptoms suggesting a central neurological cause; in this case, dizziness plus headaches and difficulty moving and speaking. The presence of these additional symptoms should always raise central causes to the top of the differential diagnosis, until proven otherwise. Specifically, dizziness plus headache should always raise the possibility of a vertebral artery dissection.

Finally, the symptoms were intermittent. Using dizziness as the anchoring symptom, this patient had an episodic vestibular syndrome (EVS) – either triggered or spontaneous.21 We do not know if there were any triggering factors for this patient, but typical ones are looking upwards or rolling over in bed at night (for BPPV) and moving from the recumbent to the sitting or standing position (for orthostatic hypotension). Some patients will volunteer these details, but if not, these questions should be asked because the responses can help distinguish a triggered EVS (e.g., BPPV, orthostasis) from a spontaneous EVS (e.g., TIA, stroke). Furthermore, episodes of dizziness that occur at night during sleep are highly predictive of BPPV, with an odds ratio of 60 in one study of 149 patients with dizziness.22

Thus, this patient’s history is consistent with an episodic vestibular syndrome following a dental procedure with additional neurological symptoms. The most common causes of spontaneous episodic vestibular syndrome are vestibular migraine, Meniere disease and posterior circulation TIA. We are not told the duration of the attacks, but this detail can sometimes help to distinguish amongst the causes of episodic dizziness. Although there is significant overlap, over 60% of TIAs last less than one hour,23 and vestibular migraine can last up to 72 hours.24 Multiple clinical factors can help distinguish TIA from vestibular migraine (see Table 4).

The Physical Examination

Ideally, the physical examination should be used to test hypotheses generated by the history. If this is a triggered episodic vestibular syndrome, then the clinician should be able to trigger it at the bedside. Because BPPV is one of the most common causes of dizziness (with a lifetime incidence of nearly 10%),25 the Dix-Hallpike test should be used liberally in patients with intermittent dizziness to elicit the physical finding of nystagmus (rapid, jerky uncontrollable eye movements).26 The details of the nystagmus are important. By convention, nystagmus is named for the direction of its fast-beating component, which can be horizontal, vertical, or torsional.

Patients with posterior canal BPPV (the most common type) have nystagmus that is triggered by the Dix-Hallpike test, transient (resolves within 60 seconds if the affected canal is kept in the tested position), and has a typical pattern (torsional and upbeating towards the patient’s head).26 However, BPPV does not cause the other neurological symptoms (i.e., headache, difficulty speaking and moving) experienced by this patient.

The other common cause of a triggered episodic vestibular syndrome, orthostatic hypotension, can be diagnosed by performing orthostatic vital signs. Some patients may not meet the specific criteria for “positive” orthostatic signs but have typical orthostatic symptoms that resolve with volume repletion or removing the inciting cause such as a new antihypertensive medication.

Thus, this patient likely had a spontaneous EVS. Between episodes, when such a patient has no symptoms and the dizziness cannot be triggered, the physical examination is not helpful because it should be normal (or baseline). However, examining for nystagmus is extremely helpful. If nystagmus is present, then further oculomotor (i.e., referring to all three cranial nerves that control eye movement) testing can help differentiate peripheral from central causes of nystagmus. Any neurological examination abnormalities (e.g., facial or limb weakness, visual field cuts, diplopia, dysarthria or hemi-sensory loss) suggest active ischemia, infarction or some other structural problem that requires further evaluation with neurologic consultation and brain and cerebrovascular imaging.

For patients without overt neurological deficits, other exam tools are useful. These include HINTS,27 HINTS-plus,28 and STANDING,29 each of which represents a combination of bedside physical examination tests. The HINTS exam, first described in 2009, includes three bedside oculomotor tests: head impulse test (HIT), nystagmus (N), and test of skew (TS). A fourth component, a bedside test of hearing by finger rub, was added in 2013 and is called HINTS-plus (see Table 3). The head impulse test has only been validated in patients who have spontaneous nystagmus (i.e., nystagmus that is present with the patient looking straight ahead or to either side but not moving their head). One important kind of spontaneous nystagmus is called direction-changing nystagmus because the direction of the fast component changes with the direction of gaze (i.e., beats to the right when the patient looks right and beats to the left when the patient looks left). Direction-changing nystagmus is always central. Spontaneous nystagmus must be distinguished from positional nystagmus, which is elicited by the Dix-Hallpike (and other) tests for BPPV, all of which involve head motion. In patients with ongoing dizziness and spontaneous nystagmus, the HINTS and HINTS-plus examinations, when performed by a trained clinician,29,30,31 reliably differentiate peripheral from central causes of dizziness.

Table 3. HINTS Plus Examination (for patients with ongoing dizziness and nystagmus)

| Test | Brief description | Reassuring findinga | Worrisome findingb |

| Head impulse test | Test of the VOR, only useful in patients who have spontaneous nystagmus (see above). It requires some tactile skill and learning. | Presence of a corrective saccade | Absence of a corrective saccade |

| Nystagmus | Test for spontaneous (non-positional) nystagmus with patient looking straight ahead or to either side, and for changing direction when looking right versus left – known as direction-changing nystagmus | Horizontal unidirectional nystagmus | Vertical, torsional or direction-changing nystagmus |

| Test of Skew | Use of alternate cover test to look for a vertical correction of gaze on uncovering one eye | Vertical correction absent | Vertical correction present |

| Test of hearing | Finger rub in a quiet room | Normal hearing on both sides | New unilateral hearing loss |

| Source: Kattah et al. (2009) Abbreviations: VOR = vestibulo-ocular reflex a Usually a peripheral vestibular problem such as vestibular neuritis b Usually a stroke or another central nervous system problem | |||

Another diagnostic algorithm, STANDING, incorporates two elements of the HINTS evaluation (spontaneous nystagmus testing and the head impulse test) but also includes bedside testing for BPPV.29 Furthermore, the STANDING algorithm formally includes testing the patient’s gait. Both HINTS testing and STANDING take only a few minutes to perform.32 However, all these bedside tests require some training to learn when to perform them, how to perform them, and how to interpret the results.

Using the HINTS or HINTS-plus battery, if any single finding is worrisome for a central cause, the patient should be evaluated for ischemic stroke and only if all four findings are reassuring, can the patient be treated for a peripheral vestibular problem. Similarly, with the STANDING algorithm, if any of the findings suggest a central cause, or if the patient cannot walk independently, they should be evaluated for stroke or other central causes. One advantage of the STANDING protocol is that it forces gait testing, which is an important element in the evaluation of every dizzy patient.

It is critical to understand that in a patient with a TIA, the neurological examination is typically normal (or baseline). In patients with transient neurological symptoms who are currently between episodes, a normal examination actually supports the diagnosis of TIA.

One other element of the presentation may have contributed to not activating a “Code Stroke” at the second visit. The patient is reported to have had “possible” seizures. Seizure-like movements are sometimes seen in patients with basilar artery stroke, often involving both upper extremities, associated with altered mentation and posturing.33 This phenomenon is not well-known, perhaps because basilar stroke is relatively uncommon and the finding does not occur in all patients.

Imaging and Laboratory Tests

In patients with isolated dizziness who have nystagmus, laboratory testing is rarely helpful. However, there are many situations in which the history or physical examination suggest a general medical cause of dizziness. One common example is a patient with dizziness, fever, hypoxia and green sputum production. Another is a patient with dizziness after starting a new antihypertensive medication and low systolic blood pressure. Yet another would be dizziness in the context of tachycardia, melena, and heavy ibuprofen use after an orthopedic injury. There are numerous other scenarios and in fact, in ED settings, approximately half of patients with a chief complaint of dizziness have one of these other general medical causes of their dizziness.34 For each of these scenarios, different tests are indicated.

Regarding imaging, non-contrast CT has a sensitivity of approximately 25% for ischemic stroke in patients presenting with dizziness.35 Reliance on a normal CT in this setting is dangerous by providing false reassurance,36 and is not recommended by clinical guidelines.37 If a TIA or stroke is the suspected diagnosis, urgent CT angiography (CTA) is recommended to define the underlying vascular lesion, according to clinical guidelines from both the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM)37 and the American College of Radiology.38

Approaches to Improving Patient Safety

As the above background suggests, misdiagnosis of patients with acute dizziness is common6,21,39 and can result in poor patient outcomes due to progression of the underlying vascular lesion or edema from an infarct in the tight confines of the posterior fossa.40,41 Misdiagnosis of posterior circulation strokes in the ED is also common, even when patients are evaluated by neurologists.42,43 Compared to anterior circulation strokes, posterior circulation strokes are missed twice as often, partly due to their non-specific symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and dizziness.42

At the same time, concern about missing a stroke in patients with dizziness can lead to overtesting, which almost always includes a non-contrast head CT. In one study of ED patients who were discharged with a diagnosis of benign dizziness, those who had CT scans at the initial visit were over twice as likely to return within one month with a stroke as those who had not been scanned.36 This finding suggests that clinicians were correctly identifying patients at higher risk of a vascular event, but then using the wrong test to reassure themselves.

It is not uncommon for emergency clinicians to use symptom-only diagnoses. After an evaluation for headache, for example, a specific diagnosis often cannot be established, and “headache of unknown etiology” is documented. However, a non-specific diagnosis of “dizziness” should only be made after potential serious causes have been excluded. In this case, posterior circulation TIA was still a possible—indeed, the most likely—diagnosis. Similarly, more detailed information from the history would be needed to diagnose “sleep paralysis” (e.g., did all the episodes occur upon awakening?). The headache, lateralizing weakness, and absence of associated fear or anxiety make sleep paralysis very unlikely. This is an example of both diagnostic anchoring and making a benign diagnosis when more dangerous diagnoses have not been ruled out.

Implicit in diagnostic anchoring or premature closure is trying to “shoehorn” a square peg (clinical findings that do not fit) into a round hole (an incorrect diagnosis). The clinician in this case may have recognized that dizziness and headache did not fit with sleep paralysis and so added those symptom-only diagnoses. Symptom-only diagnoses should be made cautiously and only after dangerous diagnoses have been reasonably excluded (e.g., diagnosing “abdominal pain of unknown etiology” after normal blood and urine testing and abdominal CT imaging).

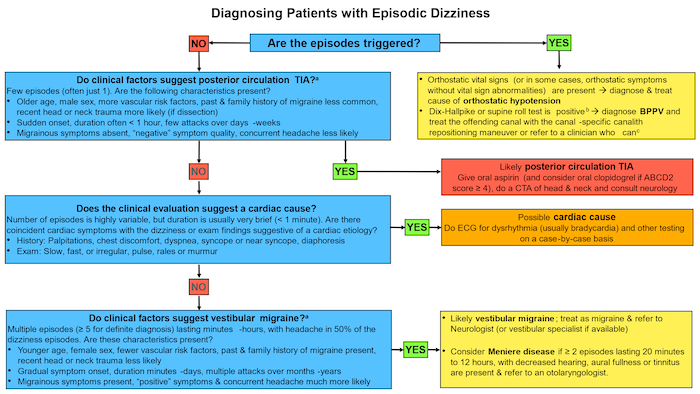

Using a more systematic approach to diagnosing patients with acute dizziness should decrease diagnostic error. Although not diagnosed in this case, vestibular migraine is the most common cause of episodic dizziness.44 There are important differences between the presentations of vestibular migraine and posterior circulation TIA (Table 4); a diagnostic algorithm for patients with episodic dizziness has been proposed (Figure 1).45

Table 4. Clinical Elements to Help Distinguish Vestibular Migraine and Posterior Circulation TIAa

| Clinical Variable | Vestibular Migraine | Posterior Circulation TIA | |

| Epidemiological Content |

|

|

|

| Timing of Symptoms |

|

|

|

| Symptom Quality |

|

|

|

| Source: Edlow and Bellolio (2024) a There is overlap for each clinical variable; no single factor perfectly distinguishes migraine from transient ischemic attack. Combinations of factors are far more likely to help distinguish these two causes of episodic dizziness or vertigo. b Diagnostic criteria include ≥5 attacks for a definite diagnosis of vestibular migraine c Photophobia, phonophobia, visual aura, nausea and vomiting | |||

Figure 1. Diagnostic Algorithm for Patients Presenting to the ED with Episodic Dizziness

Source: Adapted from Edlow and Bellolio (2024)

Note: This algorithm applies to patients who have episodes of dizziness, are currently asymptomatic and have a normal (or baseline) neurological exam at the time of evaluation--in other words, spontaneous episodic vestibular syndrome. Note that some patients with an obvious reason to be volume depleted may not have vital sign abnormalities that technically meet criteria of orthostatic hypotension and their symptoms may resolve with volume repletion. Always consider TIA in patients who present after a single episode before a clear pattern has been established

a The clinical features (see Table 2) that help to distinguish posterior circulation TIA from vestibular migraine overlap; use combinations of many elements rather than any one individual factor. Migrainous symptoms include phono- and photophobia, visual aura, nausea and vomiting

b The nystagmus in the Dix-Hallpike test that diagnoses posterior canal BPPV is upbeating torsional nystagmus beating towards the lower ear (the side being tested). The nystagmus in the supine roll test that diagnoses horizontal canal BPPV is horizontal, usually beating towards the ground; it changes direction when the other ear is tested. If it beats away from the ground, this is consistent with apogeotropic horizontal canal BPPV, but can also be seen in central mimics.

c Depending on local resources, this could be a neurologist, an otolaryngologist, a vestibular specialist or a physical therapist with vestibular expertise

Another systems-based issue is the rational use of imaging. All tests have limitations. In this case, the CT seems to have been later re-interpreted as showing some subtle findings. This highlights two issues. First, there are biological reasons for low sensitivity of CT in acute posterior circulation strokes. The fact that the MRI showed “multiple posterior circulation infarcts of various ages” suggests that some of the episodes that occurred over the preceding 3 weeks were strokes and not transient ischemia. One study found MRI to be more cost-effective than CT.46 However, it is important to recognize that even MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging misses 20% of ischemic strokes presenting as isolated dizziness in the first 48 hours.35

Secondly, radiologists occasionally make errors, especially when findings are subtle. Clear communication between clinicians and radiologists may result in more accurate interpretations. Knowing that a patient has had episodes of dizziness, headache, speech and motor symptoms, or better yet, writing in the indication for the scan, “Is there evidence of posterior circulation ischemia?”, would lead most radiologists to carefully scrutinize the structures fed by the posterior circulation and/or to recommend a better imaging test, such as MRI.

System Optimization and Quality Improvement Measures

Guidelines

In 2023, the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) published GRACE-3 (Guidelines for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the Emergency Department) for diagnosis and treatment of patients with acute dizziness in the ED.37 The topic was selected as one that was common, important to emergency clinicians,47 and associated with large practice variation.48 A committee of emergency physicians from three continents, and an otolaryngologist and a neurologist, both with special expertise in neuro-otology, authored the guidelines. Four methodologists and three patient representatives were also active members of the committee. The process, which used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) methodology, took over two years to complete.

Following GRACE-3 would likely have helped the ED physicians avoid their diagnostic error in this patient. Disseminating such information at the point of care, by having the electronic health record (EHR) “push” recommendations to clinicians, might have helped although information fatigue may limit its impact. Nevertheless, disseminating information from clinical guidelines to front-line clinicians is important.

Knowledge Gaps

The clinical evidence base related to the diagnosis of acute dizziness has exploded in the past 20 years, yet much of this new information has not been widely disseminated to clinicians. For example, the head impulse test was only described in 1988.49 These knowledge gaps need to be closed. Curricula must be updated at the medical school, post-graduate training and practicing physician levels. Some of the most useful physical examination tools such as how to perform and interpret both the head impulse test and nystagmus must be more widely taught and promoted. Knowing the presentations of very common causes of episodic dizziness, such as BPPV and vestibular migraine, should improve diagnosis of less common but more serious causes when the pattern does not fit.

Testing for nystagmus should occur in every patient with acute dizziness.5,8,39,50 The absence of nystagmus in an actively dizzy patient without some obvious cause (e.g., orthostatic hypotension) is actually more worrisome than its presence.51 This is because only 50% of patients with cerebellar strokes have nystagmus40,52 whereas nearly all patients with vestibular neuritis have nystagmus.52 How to test for and interpret nystagmus is a critical gap to close.

Testing gait should also occur in every patient with acute dizziness.39 Even with a benign, peripheral cause of dizziness, if a patient cannot walk independently, perhaps due to dehydration, it is unsafe to discharge them home. Gait testing is especially important in dizzy patients who do not have nystagmus.53 The inability to safely walk independently is highly correlated with a stroke diagnosis rather than a peripheral cause of dizziness.54

Rational Use of imaging

All imaging tests for patients with acute dizziness have important limitations. An “intelligent” EHR may push these limitations to the ordering clinician. Additionally, language about the diagnostic limitations should be incorporated into the radiologists’ interpretation.

When to Call a “Code Stroke”

A “Code Stroke” is intended to be highly sensitive but not specific. The case presentation does not make clear if the second physician was aware of the earlier ED visit. If so, the second clinician may have activated a “Code Stroke,” which would probably have expedited the CTA. Otherwise, it would not be standard practice to activate a “Code Stroke” in a patient with what may have been interpreted as status epilepticus, although “possible seizures” may well have been the seizure-like activity sometimes seen in basilar artery strokes.

Take Home Points

- When young patients have a TIA and ischemic stroke, the cause is often a cervical artery dissection or embolism through a patent foramen ovale.

- TIA is a cause of intermittent dizziness and between episodes, the neurological examination is normal.

- The presence of dizziness plus other simultaneous neurological symptoms should prompt a search for a central cause.

- Non-contrast brain CT scan has extremely poor sensitivity for identifying TIA or early ischemic strokes, especially in patients who present with dizziness.

- The abrupt onset of neurological symptoms should generally be assumed to be due to a stroke until proven otherwise.

Jonathan A. Edlow, MD, FACEP

Department of Emergency Medicine

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Professor of Emergency Medicine

Harvard Medical School

Boston, MA

References

- Drachman DA, Hart CW. An approach to the dizzy patient. Neurology. 1972;22(4):323-334. [Free full text]

- Newman-Toker DE, Cannon LM, Stofferahn ME, et al. Imprecision in patient reports of dizziness symptom quality: a cross-sectional study conducted in an acute care setting. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(11):1329-1340. [Available at]

- Kerber KA, Callaghan BC, Telian SA, et al. Dizziness symptom type prevalence and overlap: a US nationally representative survey. Am J Med. 2017;130(12):1465.e1-1465.e9. [Available at]

- Newman-Toker DE, Dy FJ, Stanton VA, et al. How often is dizziness from primary cardiovascular disease true vertigo? A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):2087-2094. [Free full text]

- Edlow JA, Gurley KL, Newman-Toker DE. A new diagnostic approach to the adult patient with acute dizziness. J Emerg Med. 2018;54(4):469-483. [Free full text]

- Gurley KL, Edlow JA. Diagnosis of patients with acute dizziness. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2021;39(1):181-201. [Free full text]

- Edlow JA. Diagnosing dizziness: we are teaching the wrong paradigm! Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(10):1064-1066. [Free full text]

- Edlow JA. Acute dizziness: A personal journey through a paradigm shift. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30(5):598-602. [Free full text]

- Kerber KA, Damschroder L, McLaughlin T, et al. Implementation of evidence-based practice for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in the emergency department: a stepped-wedge randomized trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(4):459-470. [Free full text]

- Neely P, Patel H, McTaggart J, et al. EVESTA: Emergency VESTibular Algorithm and its impact on the acute management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Emerg Med Australas. 2023;35(2):312-318. [Free full text]

- Singhal AB, Biller J, Elkind MS, et al. Recognition and management of stroke in young adults and adolescents. Neurology. 2013;81(12):1089-1097. [Free full text]

- Putaala J, Metso AJ, Metso TM, et al. Analysis of 1008 consecutive patients aged 15 to 49 with first-ever ischemic stroke: the Helsinki Young Stroke Registry. Stroke. 2009;40(4):1195-1203. [Free full text]

- Bejot Y, Daubail B, Debette S, et al. Incidence and outcome of cerebrovascular events related to cervical artery dissection: the Dijon Stroke Registry. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(7):879-882. [Available at]

- Hagen PT, Scholz DG, Edwards WD. Incidence and size of patent foramen ovale during the first 10 decades of life: an autopsy study of 965 normal hearts. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59(1):17-20. [Available at]

- El-Hajj VG, El-Hajj G, Mantoura J. Major neurological deficit following neck hyperextension during dental treatment: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Neurologist. 2022;27(6):361-363. [Available at]

- Heckmann JG, Heron P, Kasper B, et al. Beauty parlor stroke syndrome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;21(1-2):140-141. [Free full text]

- Paciaroni M, Bogousslavsky J. Cerebrovascular complications of neck manipulation. Eur Neurol. 2009;61(2):112-118. [Free full text]]

- Reuter U, Hamling M, Kavuk I, et al. Vertebral artery dissections after chiropractic neck manipulation in Germany over three years. J Neurol. 2006;253(6):724-730. [Available at]

- Weintraub MI. Beauty parlor stroke syndrome: report of five cases. JAMA. 1993;269(16):2085-2086. [Available at]

- Whedon JM, Petersen CL, Li Z, et al. Association between cervical artery dissection and spinal manipulative therapy -a medicare claims analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):917. [Free full text]

- Edlow JA. Managing patients with acute episodic dizziness. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(5):602-610. [Available at]

- Lindell E, Finizia C, Johansson M, et al. Asking about dizziness when turning in bed predicts examination findings for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Vestib Res. 2018;28(3-4):339-347. [Free full text]

- Lavallee PC, Sissani L, Labreuche J, et al. Clinical significance of isolated atypical transient symptoms in a cohort with transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2017;48(6):1495-1500. [Free full text]

- Lempert T, Olesen J, Furman J, et al. Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria (update). J Vestib Res. 2022;32(1):1-6. [Free full text]

- von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, et al. Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(7):710-715. [Available at]

- Edlow JA, Kerber K. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a practical approach for emergency physicians. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30(5):579-588. [Free full text]

- Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, et al. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke. 2009;40(11):3504-3510. [Free full text]

- Newman-Toker DE, Kerber KA, Hsieh YH, et al. HINTS outperforms ABCD2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous vertigo and dizziness. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(10):986-996. [Free full text]

- Vanni S, Pecci R, Edlow JA, et al. Differential diagnosis of vertigo in the emergency department: a prospective validation study of the STANDING algorithm. Front Neurol. 2017;8:590. [Free full text]

- Gerlier C, Fels A, Vitaux H, et al. Effectiveness and reliability of the four-step STANDING algorithm performed by interns and senior emergency physicians for predicting central causes of vertigo. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30(5):487-500. [Free full text]

- Gerlier C, Hoarau M, Fels A, et al. Differentiating central from peripheral causes of acute vertigo in an emergency setting with the HINTS, STANDING, and ABCD2 tests: a diagnostic cohort study. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(12):1368-1378. [Free full text]

- Vanni S, Nazerian P, Pecci R, et al. Timing for nystagmus evaluation by STANDING or HINTS in patients with vertigo/dizziness in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30(5):592-594. [Free full text]

- Ropper AH. 'Convulsions' in basilar artery occlusion. Neurology. 1988;38(9):1500-1501. [Free full text]

- Newman-Toker DE, Hsieh YH, Camargo CA, Jr., et al. Spectrum of dizziness visits to US emergency departments: cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(7):765-775. [Free full text]

- Shah VP, Oliveira JESL, Farah W, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of neuroimaging in emergency department patients with acute vertigo or dizziness: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the guidelines for reasonable and appropriate care in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30(5):517-530. [Free full text]

- Grewal K, Austin PC, Kapral MK, et al. Missed strokes using computed tomography imaging in patients with vertigo: population-based cohort study. Stroke. 2015;46(1):108-113. [Free full text]

- Edlow JA, Carpenter C, Akhter M, et al. Guidelines for reasonable and appropriate care in the emergency department 3 (GRACE-3): acute dizziness and vertigo in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30(5):442-486. [Free full text]

- Expert Panel on Neurological I, Wang LL, Thompson TA, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Dizziness and Ataxia: 2023 Update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2024;21(6S):S100-S125. [Available at]

- Gurley KL, Edlow JA. Avoiding misdiagnosis in patients with posterior circulation ischemia: a narrative review. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(11):1273-1284. [Free full text]

- Edlow JA, Newman-Toker DE, Savitz SI. Diagnosis and initial management of cerebellar infarction. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(10):951-964. [Available at]

- Savitz SI, Caplan LR, Edlow JA. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of cerebellar infarction. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(1):63-68. [Free full text]

- Arch AE, Weisman DC, Coca S, et al. Missed ischemic stroke diagnosis in the emergency department by emergency medicine and neurology services. Stroke. 2016;47(3):668-673. [Available at]

- Royl G, Ploner CJ, Leithner C. Dizziness in the emergency room: diagnoses and misdiagnoses. Eur Neurol. 2011;66(5):256-263. [Available at]

- Rocha MF, Sacks B, Al-Lamki A, et al. Acute vestibular migraine: a ghost diagnosis in patients with acute vertigo. J Neurol. 2023;270(12):6155-6158. [Available at]

- Edlow JA, Bellolio F. Recognizing posterior circulation transient ischemic attacks presenting as episodic isolated dizziness. Ann Emerg Med. 2024;84(4):428-438. [Free full text]

- Tu LH, Melnick E, Venkatesh AK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of CT, CTA, MRI, and Specialized MRI for evaluation of patients presenting to the emergency department With dizziness. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2024;222(2):e2330060. [Free full text]

- Kene MV, Ballard DW, Vinson DR, et al. Emergency physician attitudes, preferences, and risk tolerance for stroke as a potential cause of dizziness symptoms. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(5):768-776. [Free full text]

- Kim AS, Sidney S, Klingman JG, et al. Practice variation in neuroimaging to evaluate dizziness in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(5):665-672. [Free full text]

- Halmagyi GM, Curthoys IS. A clinical sign of canal paresis. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(7):737-739. [Available at]

- Edlow JA, Newman-Toker D. Using the physical examination to diagnose patients with acute dizziness and vertigo. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(4):617-628. [Available at]

- Machner B, Choi JH, Trillenberg P, et al. Risk of acute brain lesions in dizzy patients presenting to the emergency room: who needs imaging and who does not? J Neurol. 2020;267(Suppl 1):126-135. [Free full text]

- Wuthrich M, Wang Z, Martinez CM, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of spontaneous nystagmus patterns in acute vestibular syndrome. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1208902. [Free full text]

- Carmona S, Martinez C, Zalazar G, et al. Acute truncal ataxia without nystagmus in patients with acute vertigo. Eur J Neurol. 2023;30(6):1785-1790. [Available at]

- Carmona S, Martinez C, Zalazar G, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of truncal ataxia and HINTS as cardinal signs for acute vestibular syndrome. Front Neurol. 2016;7:125. [Free full text]