Hold That Order

The Case

A 25-year-old woman with a history of a pituitary tumor was admitted with hypernatremia. Because of her previous pituitary resection and radiation, the patient had a long history of central diabetes insipidus and difficult to manage sodium homeostasis. At home, she balanced administration of DDAVP (desmopressin acetate) and free-water boluses given by percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube to maintain a normal sodium level. Due to PEG tube dysfunction, the patient was unable to give herself free-water boluses for the 2 days prior to admission and became progressively lethargic. On admission, her serum sodium level was 159 mEq/L.

During the patient's hospitalization, the house staff team struggled with her sodium management, trying to balance the DDAVP and the free water by PEG tube. On hospital day 3, although the patient was clinically stable, she had a serum sodium level of 131 mEq/L in the afternoon. Based on this result, the intern did not want her to get additional DDAVP that day, as it would lower the sodium level further. The intern wrote the following order: "Hold DDAVP tonight."

At this academic center, a medical center policy stated that all orders to "hold" medications are interpreted as "discontinue" orders. Thus, the medication was discontinued in the medication administration record (MAR) and in the pharmacy records. The intern was not notified of the discontinuation of the DDAVP.

The next day, the patient's sodium level slowly rose to 144 mEq/L in the afternoon, and the team wanted the patient to receive her evening DDAVP. The intern assumed that the patient would receive the evening dose of medication because her order had stated to hold it for only 1 day.

The patient was not given the DDAVP, and the following morning her sodium level was 154 mEq/L. She was slightly lethargic and less interactive than usual and was given an urgent dose of DDAVP. Her sodium level was closely monitored for the next 24 hours. She did not experience any serious or long-term consequences.

The Commentary

This case demonstrates some of the potential problems associated with physician orders to temporarily stop or "hold" the administration of particular medications in the inpatient setting. What appears to be a simple and straightforward order can lead to a variety of breakdowns in the medication administration process and potentially lead to patient harm, as it did in this case.

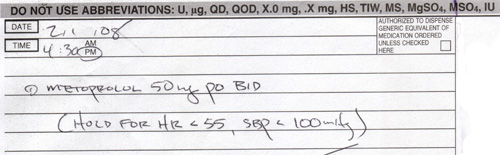

"Hold" orders (or temporary stop orders) are employed in a number of different situations in health care settings. Most frequently, hold orders are written for medications associated with specific monitoring parameters or with certain conditions that would require a medication to be stopped altogether. Antihypertensives or other medications that affect blood pressure or heart rate are often ordered to be held when blood pressures or heart rates fall below normal values to avoid worsening of the vital signs (Figure). Hold orders are also commonly used around the time of procedures (e.g., surgery, cardiac catheterization), where some medications need to be stopped prior to a procedure and then restarted upon completion. For example, oral medications for diabetes (which can lead to hypoglycemia if patients are not eating) might be held on the day of the procedure with the intention of starting them again afterward.

Unfortunately, medication errors associated with hold or temporary stop orders are common. Reporting agencies have been able to identify the most common culprit medications. According to the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Reporting System (PA-PSRS), the most common classes of medications involved in errors associated with the use of hold orders include:

- Anticoagulants, including warfarin (Coumadin), heparin, enoxaparin (Lovenox), and dalteparin (Fragmin), were mentioned in one-third of all medication error reports involving hold orders in PA-PSRS.

- Antihypertensives such as enalapril, amlodipine, atenolol, and metoprolol were involved in more than 16% of reports.

- Antidiabetic agents such as insulin, glyburide, and repaglinide (Prandin) were associated with 15% of the reports.(1)

Safety organizations have also published individual case reports similar to the case here in which hold orders led to patient harm. In one case reported to the USP-ISMP medication error reporting program (MERP), an elderly woman was in the hospital for a number of days when a doctor requested a gastroenterology consult to see if the patient was bleeding. The physician wrote an order to "Hold Coumadin" without any monitoring parameters. Based on the organization's protocol, the pharmacy interpreted this order as an order to discontinue the warfarin, so it was taken off the medication list. The gastroenterologist performed the endoscopic procedure and, after the procedure, wrote orders for the patient to receive all of the previous treatments and active medications using the patient's MAR as a reference. However, the warfarin had been discontinued, and the busy physician did not reorder the medication. Therefore, the warfarin was not restarted after the procedure. Six days later, the patient suffered a stroke, which was directly related to lack of anticoagulation.(2)

In another case reported to MERP, a doctor wrote an order to hold enoxaparin (Lovenox) before a patient was to undergo a pacemaker implant procedure. This prescriber also wrote an order to resume the enoxaparin 48 hours after the procedure. Unfortunately, the order specifying when to restart the medication was not transferred to the MAR, and thus it seemed that the physician wanted to only hold the dose prior to the procedure. Therefore, the nurse gave the medication to the patient when he returned to the intensive care unit (ICU) after the procedure.(2) Although the patient suffered no consequences, administration of enoxaparin put him at risk for life-threatening bleeding after the procedure.

Why do errors occur in association with hold orders? From a physician standpoint, the desire to temporarily stop a medication is common, and the process seems as if it should be straightforward. Yet errors that arise with hold orders may occur during all phases of the medication-use process. For example, breakdowns that occur during the transcribing or data entry process, as documented by the PA-PSRS, include:

- Transcribing process

- When hold orders, or the parameters for the hold order, are not transcribed to the MAR

- When MARs are recopied and the hold order and/or corresponding parameters are omitted

- When hold orders are not adequately communicated to the pharmacy

- When no hold parameters are written by the ordering provider (as in this case)

- Order entry

- When hold orders are missed by the pharmacy and are not entered into the computer system (1)

Errors that occur during the prescribing process include the timing at which the hold order was written by the prescriber. For example, errors have occurred when hold orders were not communicated or transcribed until after the dose of medication was administered.

Conversely, cases are documented in which failure to hold a medication has resulted in harm to patients. One event reported by MERP involved a patient with diabetes who was receiving continuous enteral feedings as well as subcutaneous insulin. The patient was to undergo a computed tomography (CT) scan, and therefore the feedings were held. Unfortunately, there was no order to hold the insulin; it was administered, and the patient became profoundly hypoglycemic. The patient was given intravenous dextrose and suffered no lasting consequences but certainly could have been harmed by the failure to hold the insulin.(3)

What can institutions do to prevent errors associated with temporary stop orders? Recommendations suggested in the literature include the following:

- Orders to hold a medication without specific instructions on when or how to restart the medication should be prohibited. If a hold order does not provide specific restarting parameters, the nurse or pharmacist should clarify that order with the original prescriber to see if there are specific criteria that can be added. If there are no criteria indicated, the drug should be discontinued. Providers should be aware that when medications are discontinued in the acute care setting, the medications may disappear from pharmacy systems or nursing profiles, and resuming the order may be forgotten.

- Organizations should consider generating a daily summary of medications that have been prescribed for a specific patient that can be reviewed daily by physician or allied health professional. These summaries could include both active and recently discontinued medications. These lists could prompt prescribers to reorder medication therapies that were discontinued for procedures or need to be renewed prior to discharge from the hospital.

- Orders to hold medications until after a procedure can be problematic and should generally be prohibited. In addition, orders to "resume all pre-op medications" or "continue all prior medications" should be avoided. These types of orders transfer the responsibility of determining the patients' medications to nurses and pharmacists at the most error-vulnerable periods in the health care continuum: admission, postprocedure, transfer to a different level of care, and discharge.(4) All medications should be reviewed by prescribers and new orders written after any transfer to different care areas. The newly written orders should be reconciled with the previously prescribed medications. (For more discussion on medication reconciliation, please see the AHRQ WebM&M commentaries "Medication Reconciliation: Whose Job Is It?" and "Reconciling Doses.") This process follows the Joint Commission's National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG) on medication reconciliation.(5) If the organization has a computerized prescriber order entry (CPOE) system, it may be possible to place orders from before the procedure in a queue and rewrite orders for medications by simply "releasing" each needed drug. Standardized postprocedure order sets can help if there are prompts to remind prescribers to restart medications that are commonly held, such as anticoagulants.

- In ambulatory practice settings, prescribers should establish a process to track medications they wanted temporarily stopped and a system for contacting patients with instructions for when medications should be restarted. Patients should be told to expect a call and also given instructions regarding when medications should be stopped and/or restarted.(6)

In the case presented in this commentary, a 25-year-old woman experienced elevated sodium levels after DDAVP therapy was placed "on hold" for one night, but there were no orders to specify if or when the order should be resumed. In this situation, the intern was unfamiliar with the organization's policy that all hold orders are considered to be discontinued. Many of the recommendations listed above could have helped to prevent this error from occurring. For example, if the intern further clarified the order to indicate what should be done with the patient's DDAVP therapy after "tonight." The intern could have indicated to restart therapy the next day or based on the patient's sodium levels, along with the initial hold order. In addition, a review of this patient's daily summary of medications would have provided an opportunity to review all of the patient's medications, including those that were held or discontinued, to determine if these medications should be restarted and/or when they should be reinitiated.

Take-Home Points

- Temporary hold orders can lead to multiple errors and complications in the medication administration process.

- Hold orders can lead to problems with medication prescribing, transcription, or order entry.

- Providers should avoid the use of hold orders unless absolutely necessary.

- Prescribers should track medications that they want temporarily stopped and have a system for contacting patients with instructions for when medications should be restarted.

- Hospitals should prohibit all hold orders that do not provide specific instructions on when to resume the medication.

Matthew Grissinger, RPh Director, Error Reporting Programs Institute for Safe Medication Practices

References

1. Hold on to those orders. PA-PSRS Patient Safety Advisory. March 2006;3:33-34. Available at: http://www.psa.state.pa.us/psa/lib/psa/advisories/mar_2006_advisory_v3_n1.pdf.

2. Medication orders: don't put me on hold. ISMP Medication Safety Alert! Acute Care Edition. March 24, 2005;10:6. Available at: http://www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20050324.asp.

3. Cultural diversity and medication safety. ISMP Medication Safety Alert! Acute Care Edition. September 4, 2003;8:18. Available at: http://www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20030904.asp.

4. Orders to "continue previous meds" continue a long standing problem. ISMP Medication Safety Alert! Acute Care Edition. November 1, 2000. Available at: http://www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20001101.asp.

5. National Patient Safety Goals. Joint Commission Web site. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/ NationalPatientSafetyGoals/07_npsg_facts.htm.

6. Cohen MR, ed. Medication Errors. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmaceutical Association; 2006:187. ISBN: 1582120927.

Figure

Figure. Example Hold Order.