Direct Oral Anticoagulants are High-Risk Medications with Potentially Complex Dosing

Giannini J, Wong M, Dager W, et al. Direct Oral Anticoagulants are High-Risk Medications with Potentially Complex Dosing. PSNet [internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2020.

Giannini J, Wong M, Dager W, et al. Direct Oral Anticoagulants are High-Risk Medications with Potentially Complex Dosing. PSNet [internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2020.

The Case

A male patient with a history of right axillofemoral and right to left femoral-femoral bypasses in September 2018 presented to the hospital 4 months later with right calf pain and evidence of popliteal artery occlusion. He underwent thrombolysis and thrombectomy and was discharged five days later. He was instructed to take rivaroxaban 15 mg twice daily for 19 days, to complete the full 21 day loading phase, and then 20 mg daily thereafter. The prescription and written instructions on the After-Hospital Summary (AHS) were correct, but nurse-generated check marks used when educating the patient on discharge medications incorrectly indicated that the 20 mg daily dose was to be given twice daily. This visual aid was included in the AHS indicating that rivaroxaban was to be administered at 9am and 9pm for both the 15 mg and 20 mg strengths. Relying upon the easy visual instruction sheet included in the AHS, as opposed to the prescription label, the patient reported taking 15 mg twice daily for 19 days (as prescribed) and then took 20 mg twice daily from the end of January until mid-February. This resulted in a six-day lapse between the day he ran out of his rivaroxaban and the day he could refill the 20 mg maintenance dose. He was readmitted shortly thereafter and found to have developed recurrent right popliteal and posterior tibial occlusion.

The Commentary

By Janeane Giannini, PharmD, Melinda Wong, PharmD, William Dager, PharmD, Scott MacDonald, MD, and Richard H. White, MD

This patient was prescribed rivaroxaban to prevent arterial re-thrombosis following thrombolysis and thrombectomy of a popliteal occlusion, which is an off-label use of this drug. The prescribed dosing of rivaroxaban was the package insert recommendation for the treatment of acute venous thrombosis, specifically 15 mg twice daily for 21 days, followed by 20 mg daily thereafter for 3-6 months. In comparison, the recommended dose of rivaroxaban for the prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation is 20 mg a day unless the patient has a calculated creatinine clearance (CrCl) of < 50 ml/min, when the recommended dose is 15 mg a day. For patients with a CrCl <15 ml/min, rivaroxaban should not be prescribed.1 Rivaroxaban does have an approved indication for use in patients with chronic peripheral arterial disease (PAD) or coronary artery disease (CAD); the dose of rivaroxaban for the chronic PAD/CAD indication is 2.5 mg twice daily in combination with low-dose aspirin (75-100 mg) once daily.2

In this case, a prescription was written for acute venous thromboembolism (VTE) doses of rivaroxaban (even though this patient had a recent arterial thrombosis) and sent to the pharmacy, where it was filled as written and the label on the pill container showed the correct dosing (for acute VTE). The nurse who discussed the AHS instructions accidentally checked off that both the 15 mg tablets AND the 20 mg tablets needed to be taken twice a day. Hence the patient took a dose of 40 mg of rivaroxaban each day after the 21st day of therapy, which was 8 times higher than the dose recommended for patients with PAD, and 2 times higher than the recommended dose to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Because of this error, the patient ran out of rivaroxaban early and was unable to obtain a refill (due to payer rejection) until he had gone 6 days without taking any anticoagulant. Unfortunately, this long unexpected gap in treatment led to a re-thrombosis of his popliteal artery.

Role of Direct-acting Oral Anticoagulants versus Other Anticoagulants

Thrombosis involving either the arterial or venous circulation is the principal pathologic event that leads to the majority of serious or fatal vascular outcomes worldwide.3 Anti-thrombotic agents include both anti-platelet agents and anticoagulants. The only oral anticoagulant that was available in the United States between 1954 and 2010 was warfarin or a similar coumarin drug dicumarol. New oral anticoagulants first became available in the USA in 2010 when dabigatran was approved. Rivaroxaban was approved for use in 2011 and apixaban was approved in 2014. Edoxaban and betrixaban are two more recently approved anticoagulants.4 These Direct-acting Oral Anti-Coagulants (DOACs) directly inhibit either thrombin (dabigatran) or activated Factor Xa (all other DOACs). DOAC drugs should not be considered simply as substitutes for warfarin because their mechanism of action is quite different. DOAC agents interfere at a specific step in the coagulation cascade whereas warfarin works by lowering the level of four clotting factors (II, VII, IX and X).

Although DOACs are touted to be much easier to dose and monitor than warfarin, the dosing of DOACs is actually complex. Physicians and other health care providers likely need more education about DOACs than warfarin because anticoagulation clinics have essentially taken over the management of warfarin dosing, whereas primary care providers oversee management of patients who are prescribed a DOAC. Indeed, health care systems need to train a cadre of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists and give them ready access (e.g. via EHR) to key information about the indications and the nuances of the use of these agents. Dosing is particularly challenging because the optimal DOAC dose depends on several factors including the indication (atrial fibrillation, VTE treatment, or VTE prevention), level of renal function, body weight/body mass index, and age.

Guidelines now recommend use of a DOAC as a first line therapy in the management of VTE.5 The benefits of using a DOAC include: no need to routinely monitor the drug level or its anticoagulant effect, a relatively short half-life (half-life is much longer for betrixaban), few significant drug interactions, and a significantly lower incidence of intracranial bleeding compared with warfarin. However, because patients taking DOACs are not closely monitored, they must receive thorough education at the outset of treatment to ensure they understand how to use the drug and when to seek medical attention. Patients need to know that the relatively short drug half-life means that they cannot miss taking their daily dose(s) because this may lead to the development of a clot.

Compared to warfarin, DOAC drugs are not as effective in preventing thrombosis for some conditions. For example, warfarin is the only oral anticoagulant approved for use in patients with a mechanical heart valve.6 Also, recent studies have shown that warfarin is superior to the DOAC rivaroxaban in preventing recurrent thrombosis in patients with anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome (APS).7,8 And, very recently, non-experimental evidence suggesting that warfarin is more effective than DOACs in preventing strokes and systemic emboli among patients with left ventricular thrombi was published.9 Thus, at least until there are published clinical trials that directly compare a DOAC to warfarin and confirm either superiority or non-inferiority, substitution of a DOAC for warfarin is ‘off-label’ and not recommended. Pertinent to the case being discussed, there have been no clinical trials that have compared warfarin to a DOAC agent in the initial treatment of acute arterial thrombosis.10 Rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) plus aspirin (100 mg daily) has been approved for treatment of patients with chronic peripheral artery disease (PAD) based on a significant reduction in total mortality and cardiovascular mortality in patients taking it as compared to patients taking warfarin.11 In combination with anti-platelet drugs, low dose rivaroxaban use is associated with a lower incidence of bleeding among patients with acute coronary syndrome, when compared with dual antiplatelet treatment.6

Assessment of DOAC use in End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) is limited. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data with single-dose and multiple-dose administration have been reported for rivaroxaban and apixaban, respectively, but, no randomized control trials assessing both efficacy and safety of these drugs for ESRD have been conducted. Thus, application in this population is not robust. Apixaban, at two different doses, has been studied in human subjects with ESRD (5mg twice daily or 2.5 mg twice daily).12,13 A meta-analysis has shown that use of apixaban in patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease appears to be associated with: no difference in the incidence of major bleeding compared to warfarin, a lower incidence of minor bleeding, and no difference in the incidence of stroke or VTE events.12 However, neither the FDA nor guidelines from any major medical/pharmacological society currently recommend use of apixaban over warfarin in patients with a CrCl < 15 ml/min.5 Additionally, drug interactions and significant organ failure may also prolong the elimination of DOACs from the circulation.

Given the complexity of DOAC dosing, the risk of either inadequate anticoagulation or excessive anticoagulation, and the lack of monitoring parameters for DOACs such as the International Normalized Ratio (INR) which reflects the therapeutic effect of warfarin, prescribers often struggle with problems in day-to-day management of these drugs. For example, interruptions in therapy can occur due to patient non-adherence, insurance-related problems (as in this case), procedures involving spinal/epidural anesthesia or puncture, and surgeries or trauma. Prescribers should have access to resources to help them decide which interruptions require urgent intervention, such as starting a low molecular weight heparinoid medication to “bridge” the gap in anticoagulation until the DOAC regains therapeutic efficacy, and which interruptions do not. In cases where a heparin drip is used as a bridge, the effect of a DOAC on Anti-Xa monitoring must also be considered. In retrospect, this patient might have benefited from a more timely response to the interruption of therapy that had resulted from miscommunication about dosing.

Systems Change Needed/Quality Improvement Approach

Medical care is complex and best practices frequently change, making it difficult for providers to keep up with the most current evidence-based and FDA-approved drug treatments. Computerized clinical decision support mechanisms, such as order sets, should be used to help users avoid errors of commission or omission by prompting situation-specific orders and details, as well as recommending collateral orders.14 When these support mechanisms are embedded in common workflows that prescribers use daily in their Electronic Health Records (EHR), they ‘nudge’ or ‘direct’ appropriate prescribing behavior.

Another key aspect of creating proper order sets is to link the correct set of orders to specific indications, especially for medications that require different dosing regimens depending on patient circumstances and characteristics. An order set can address a broad category of interventions, such as anticoagulation treatment, and user choices within the order set can help the prescriber to select the best choice for a particular patient. Examples of specific indications include: VTE treatment vs atrial fibrillation treatment, using warfarin vs DOACs, normal vs. impaired renal function, weight adjustment and initial treatment vs. chronic treatment. Alerts can be generated along with order sets when there are important potential drug interactions. Relevant variables, such as status of a patient’s renal function, can be determined from data already in the electronic record. If done well, order sets can decrease cognitive burden, prevent errors and minimize the time involved in completing clinical work.15

Prescriptions sent to retail pharmacies from hospitals at discharge or physician’s offices can include similar details if the healthcare provider indicates the condition being treated, the acuity of that condition, and the patient’s current weight and renal function. For this particular case, an order set or prescription should not have included “acute arterial occlusion” as an indication because there are currently no guideline-based recommendations to treat acute arterial thrombosis with a DOAC. Instead, current recommendations for patients with acute arterial occlusion include use of intravenous anticoagulants and single or dual anti-platelet agents (including vorapazar).16

Approach to Improving Safety

In addition to ensuring health care workers are educated about the current best practices, educating patients and caregivers is also important, especially upon hospital discharge. Studies have shown that transitional periods represent critical points at which patients are placed at higher risk of adverse events due to medication errors, with over half of all hospital medication errors occurring at discharge or transfer to the care of another physician.17,18 As patients return home after a discharge from an inpatient stay, new challenges arise as they resume responsibility for obtaining and managing their medications; ineffective planning and coordination of care at home can thus lead to adverse events and contribute to increased risk of hospital readmissions.19

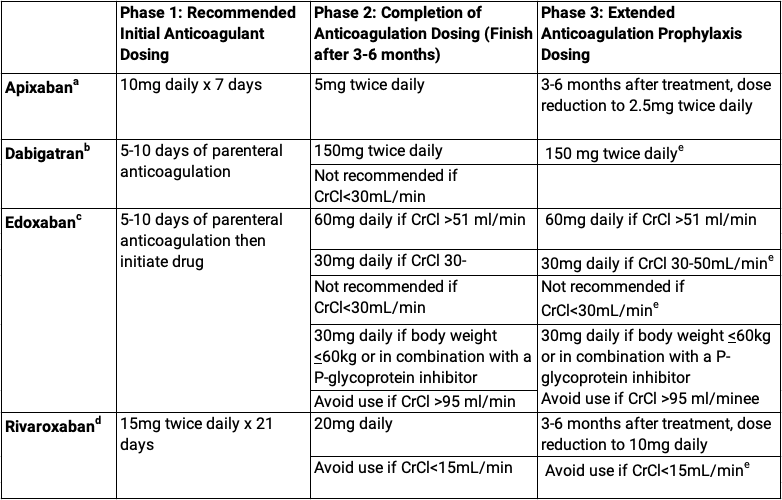

Both health care providers and patients must be properly educated about using DOACs. Dosing of DOACs is not straightforward as it varies by the drug, the indication, acuity, age, weight, renal function and concomitant use of other medications. The dosing for acute venous thrombosis is particularly complex as the table below illustrates.

DOAC Dosing for Venous Thromboembolism

aData adopted from apixaban package insert20

bData adopted from dabigatran package insert21

cData adopted from edoxaban package insert22

dData adopted from rivaroxaban package insert1

eNot specifically FDA approved for prophylactic dose

The AHS provided at the time of discharge plays a crucial role in patient education as it includes free-text or EHR-generated instructions regarding the patient’s post-discharge plan of care. While enhancements to EHR functionalities often help provide more effective and efficient care for patients, they may be associated with disadvantages as well. For example, the EHR customization in the current case was the ability to use checkmarks to denote the number and timing of doses to be taken each day. The checkmarks were added with the intent of illustrating dosing instructions through visual cues. However, this manual manipulation of the medication list was what introduced erroneous instructions into the AHS. Therefore, the approach to systems improvement should be multi-faceted. One improvement would be to provide standardized and robust training in using EHR functionalities to all care providers. If providing sufficient or timely EHR training is not feasible, another approach would be to turn off the ability to personalize medication lists in the EHR and thereby reduce opportunities for omission, duplication, or disparate information.23

Standardized teaching materials can also be a useful resource for both providers and patients. Pamphlets and videos ensure that information is delivered consistently and guide pertinent counseling points. Such materials also allow the patient to reinforce their understanding of important information relevant to their recovery after discharge.24 This reinforcement feature may be especially helpful as information retention is often low during the hectic discharge phase. It should be emphasized that these educational visual aids should be used as reinforcement though and not as a replacement for giving verbal instructions to the patient.25 During such verbal patient counseling sessions, important information that should be mentioned about the anticoagulant(s) that patient has been prescribed would include the following:

- Mechanism of action, described in patient-friendly terms

- Dosing instructions for the patient-specific indication, including taper schedule if applicable

- Instructions on what to do in case of an upcoming procedures or being prescribed new medications while on a blood thinner

- Instructions on how to handle missed doses of medication

- Medication-specific counseling points (e.g. higher doses of rivaroxaban must be taken with food1, dabigatran must be kept in original bottle and capsule not opened or chewed21)

- Typical or minimal duration of the therapy despite resolution of symptoms

- Symptoms of major versus minor bleeding and when to seek medication attention

- Common over-the-counter medications that should be avoided while on an anticoagulant

- Food, drug, or alcohol interactions common when taking anticoagulant medications

- Importance of medication adherence and compliance with obtaining laboratory work for monitoring

- Cost considerations including use of coupons or assistance programs, if appropriate

All standardized educational materials should be made readily available and accessible to all staff members as well as consistently provided to patients.

In addition to standardized teaching materials, another important component of patient education is consideration of each patient’s health literacy. Misunderstanding medication instructions can often be attributed to limited health literacy. A highly effective strategy for ensuring patient understanding is use of the teach-back method, in which the patient explains the medication and instructions back to the care provider in their own words.26 In the present case, the patient was provided with correctly prescribed instructions on the AHS, but also with erroneously checked visual instructions. When appropriately used, the teach-back method can simultaneously reveal misunderstanding as well as the root cause of the confusion, and thus identify the need for further personalized instruction and reinforcement.27 For example, asking the patient in this case “Can you tell me how many times a day you will take this medication?” probably would have focused attention on the incorrectly marked dosing frequency in the AHS. Patient education should not be provided until after the discharge plan has been finalized to prevent confusion that could be caused by last minute changes, and should ideally take place in conjunction with bedside medication delivery to eliminate any problems that patients may encounter at a retail pharmacy, such as high prices or limited stock.28 Delivery of bedside discharge education should be free of distractions and should include a member of the patient’s family whenever possible.

When a DOAC is prescribed for initial VTE treatment, higher doses may be given initially (e.g., for the first 7 days for apixaban and first 21 days for rivaroxaban) and then lowered. Alternatively, dabigatran and edoxaban require a short course of low-molecular-weight-heparin or regular heparin prior to initiation of oral therapy. For apixaban and rivaroxaban, it is best if the prescriber orders a “Starter Pack,” if possible, to guide patients in transitioning between the loading and maintenance doses.23 In a starter pack, each day’s dose is prepackaged and laid out for the patient, thereby minimizing errors other than missing a dose entirely. This approach also makes it easier for physicians to write the prescription and to ensure proper dose change on the correct day. If a patient being discharged has already started taking the DOAC as an inpatient, but a starter pack is not available, then clear written instructions and specific dates, e.g. for the dose change, should be provided. For example, the care provider might write: “You will be taking rivaroxaban 15 mg twice daily from X to Y date, then on Z date, you will then start taking only 20 mg daily.” Verbal education and instructions should still be provided as well, with specific attention drawn to the date(s) when the change in dose should take place.

Some institutions that are associated with an anticoagulation clinic to monitor warfarin patients may go a step further and provide that service to DOAC patients. An anticoagulation clinic can: (1) assist the patient and the clinician in selecting the most appropriate drug and dose from the growing list of anticoagulant options (including warfarin), (2) help patients minimize the risk of serious bleeding complications through careful long-term monitoring and peri-procedural management, (3) encourage ongoing adherence to these life-saving medications, and (4) assist with cost issues, especially for Medicare patients whose insurance may change yearly or fall into the coverage gap.29 Enrolling a patient in this type of program also reinforces the education they were provided in the hospital and gives them a point of contact for any questions that may arise regarding use of the DOAC.

Take-Home Points

- Prescribing DOACs can be challenging as dosing varies based on a multitude of factors such as indication, age, weight, renal function, loading phase, and maintenance phase

- Computerized clinical decision making at the time of order entry may promote adherence to guideline recommendations and mitigates the risk of errors when prescribing of DOACs

- Staff should be fully trained in EHR functionalities to prevent disparate practices leading to errors

- Standardized teaching materials about medications are helpful resources for ensuring patients are consistently receiving pertinent information regarding their medication(s)

- Using the teach-back method is a good way to assess a patient’s health literacy and retention of information and medication-related instructions

- Errors associated with prescribing DOACs with complex dosing regimens, such as rivaroxaban and apixaban for acute VTE, may be mitigated by using “starter packs”

- Ambulatory care anticoagulation programs may improve patient safety by providing continued monitoring and assessment of patients on DOACs

Janeane Giannini, PharmD

Senior Clinical Pharmacist

Department of Pharmacy Services

UC Davis Health

Melinda Wong, PharmD

Clinical Pharmacist

Department of Pharmacy Services

UC Davis Health

William Dager, PharmD

Cardiovascular Pharmacist Specialist

Department of Pharmacy Services

UC Davis Health

Scott MacDonald, MD

EHR Medical Director

Clinical Informatics

Department of Medicine

UC Davis Health

Richard White, MD

Medical Director, Anticoagulation Service

Department of Internal Medicine

UC Davis Health

References

- XARELTO [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2020.

- Eikelboom, J, Connoly, S, Bosch, J. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in stable cardiovascular disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377(14):1319-1330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709118

- Raskob GE, Angchaisuksiri P, Blanco AN, Buller H, Gallus A, Hunt BJ, Hylek EM, Kakkar A, Konstantinides SV, McCumber M, Ozaki Y, Wendelboe A, Weitz JI; ISTH Steering Committee for World Thrombosis Day. Thrombosis: A major contributor to global disease burden. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2363-2371. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304488

- Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/index.cfm Accessed June 8, 2020.

- Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016;149:315-352.

- Sikorska J, Uprichard J. Direct Oral Anticoagulants: A Quick Guide. European Cardiology Review 2017;12(1):40–5. doi: 10.15420/ecr.2017:11:2

- Ordi-Ros J, Sáez-Comet L, Pérez-Conesa M, et al. Rivaroxaban Versus Vitamin K Antagonist in Antiphospholipid Syndrome: A Randomized Noninferiority Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:685–694. doi: 10.7326/M19-0291

- Pengo V, Denas G, Zoppellaro G, et al. Rivaroxaban vs. Warfarin in high-risk patients with antiphospholipid syndrome. Blood. 2018;132(13):1365-1371. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-04-848333.

- Robinson AA, Trankle CR, Eubanks G, et al. Off-label Use of Direct Oral Anticoagulants Compared With Warfarin for Left Ventricular Thrombi. JAMA Cardiol. Epub 2020 Apr 22. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0652

- Olinic DM, Tataru DA, Homorodean C, et al. Antithrombotic treatment in peripheral artery disease. Vasa. 2018 Feb; 47(2):99-108. doi:10.1024/0301-1526/a000676.

- Bonaca MP, Bauersachs RM, Anand SS, et al. Rivaroxaban in Peripheral Artery Disease after Revascularization. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1994-2004. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2000052

- Chokesuwattanaskul R, Thongprayoon C, Tanawuttiwat T, et al. Safety and efficacy of apixaban in patients with end-stage renal disease: Meta-Analysis. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2018; 41: 627-634. doi:10.1111/pace.13331

- Wang X, Tirucherai G, Marbury TC, et al. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of apixaban in subjects with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56(5):628-636. doi: 10.1002/jcph.628

- Ahuja T, Raco V, Papadopoulos J, Green D. Antithrombotic Stewardship: Assessing Use of Computerized Clinical Decision Support Tools to Enhance Safe Prescribing of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Hospitalized Patients. J Patient Saf. 2018; Volume Publish Ahead of Print. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000535

- Avansino J and Leu MG. Effects of CPOE on provider cognitive workload: a randomized crossover trial. Pediatrics. 2012; 130(3) e547-e555. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3408.

- Bonaca M, Antonio Gutierrez J, Creager M, et al. Acute limb ischemia and outcomes with vorapaxar in patients with peripheral artery disease: results from the trial to assess the effects of vorapaxar in preventing heart attack and stroke in patients with atherosclerosis-thombolysis in myocardial infarction 50 (TRA2°P-TIMI 50). Circ. 2016: 133(10):997-1005. doi:0.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019355.

- Bandres M, Mendoza M, Nicolas F, et al. “Pharmacist-led medication reconciliation to reduce discrepancies in transitions of care in Spain.” Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35:1083-1090.

- Walker P, Bernstein S, Jones J, et al. “Impact of a pharmacist-facilitated hospital discharge program: a quasi-experimental study.” Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):2003-10.

- Sen S, Bowen J, Ganetsky V, et al. “Pharmacists implementing transitions of care in inpatient, ambulatory and community practice settings.” Pharm Pract. 2014; 12(2):439-447.

- ELIQUIS [Package Insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2020.

- PRADAXA [Package Insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2020.

- SAVAYSA [Package Insert]. Basking Ridge, NJ: Daiichi Sankyo Inc.; 2020

- Wright A, Schiff G. The lost start date: an unknown risk of E-prescribing. Patient Safety Network. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/web-mm/lost-start-date-unknown-risk-e-prescribing. October 2019. Accessed May 3, 2020

- Margolis H. Boosting memory with informational counseling: Helping patients understand the nature of disorders and how to manage them. ASHA Lead. 2004:9(14):10-28. doi.10.1044/leader.FTR5.09142004.10

- Marcus C. Strategies for improving the quality of verbal patient and family education: a review of the literature and creation of the EDUCATE model. Health Pyschol Behav Med. 2014.2(1):482-495.

- Effectiveness of the teach-back method in improving self-care activities in postmenopausal women. Prz Menopauzalny. 2018 Mar; 17(1):5–10. doi: 10.5114/pm.2018.74896

- Schillinger D. Lethal Cap. Patient Safety Network. Lethal Cap. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/web-mm/lethal-cap. March 2004. Accessed May 11, 2020.

- Lash D, Mack A, Jolliff J. Meds‐to‐Beds: The impact of a bedside medication delivery program on 30‐day readmissions. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2019. 2(6):674-680. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1108

- Barnes GD, Nallamothu BK, Sales AE, Froehlich JB. Reimagining Anticoagulation Clinics in the Era of Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:182-185. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002366